515 Edgecombe Avenue is located in a neighborhood steeped in history. The “combe” in Edgecombe is derived from an Anglo-Saxon word meaning “hill”.

Morris-Jumel Mansion

Just two blocks north of our building is the historic Morris-Jumel Mansion. General Washington used Morris-Jumel Mansion (MJM) as his headquarters during the fall of 1776. It was during this period that the General’s troops forced a British retreat at the Revolutionary War Battle of Harlem Heights.

The house was built eleven years before the revolution, in 1765, by British Colonel Roger Morris and his American wife, Mary Philipse. The breezy hilltop location proved an ideal location for the family’s summer home. Known as Mount Morris, this northern Manhattan estate stretched from the Harlem to the Hudson Rivers and covered more than 130 acres. Because they were loyal to the crown, the Morrises were eventually forced to return to England.

During the war, the hilltop location of the Mansion was valued for more than its cool summer breezes. With views of the Harlem River, the Bronx, and Long Island Sound to the east, New York City and the harbor to the south, and the Hudson River and Jersey Palisades to the west, Mount Morris proved to be a strategic military headquarters. Shortly after the Battle of Harlem Heights, Washington and his troops left the Mansion and, for a time, it was occupied by British and Hessian forces.

President Washington returned to the Mansion on July 10, 1790, and dined with members of his cabinet. Guests at the table included two future Presidents of the United States: Vice President John Adams and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of War Henry Knox also attended.

The Mansion is built in the Palladian style, with a second story balcony and a two-story front portico supported by classical columns. The two-story octagon at the rear of the house is believed to be the first of its kind anywhere in the colonies. The first floor of the 8,500 square foot house features rooms for family and social gatherings, and includes the parlor in which Madame Eliza Jumel married Aaron Burr in 1833. Across the hall stands the dining room where Washington likely entertained his guests in 1790. At the far end of the hall, the octagonal drawing room, or withdrawing room as it is properly known, provided a grand setting for social gatherings. Bedrooms on the second floor include those of George Washington, Eliza Jumel, and Aaron Burr. The basement houses the colonial-era kitchen and tells the story of domestic servitude at the Mansion. The room features the original hearth and a bee-hive oven as well as a collection of early American cooking utensils. Through architecture and a diverse collection of decorative arts objects, each room of the Morris-Jumel Mansion reveals a specific aspect of its colorful history from the 18th through the 19th centuries.1

Coogan’s Bluff

Coogan’s Bluff, a large cliff extending northward from 155th Street in Manhattan, once was the site of the fabled Polo Grounds, the home of the New York Giants (baseball) for over 5 decades, and the first home of the New York Mets.

To the north of Highbridge park is a wooded area within which lies a landmark schist rock that pokes through the dirt called Coogan’s Bluff. It is named after James Coogan, Manhattan Borough President, who sold the land to New York Giants owner John T. Brush, who moved the Giants to the second Polo Grounds in 1891.

Baseball soon established itself as the quintessential American game, and the New York Giants made significant contributions to 20th century baseball lore. Mel Ott (1909–1958) and Willie Mays (b.1931) are thought to be among the finest players of all time; and the names of Christy Mathewson (1878–1925) and Carl Hubbell (1903–1988) are still mentioned whenever great pitchers are discussed. The Giants also provided baseball with one of its most dramatic moments: “the shot heard round the world.” In 1951, the Giants and their arch-rivals the Brooklyn Dodgers were in the ninth inning of the deciding game in a play-off to determine the National League pennant winner. With two outs left in the game, the Dodgers were ahead 4–2 when Bobby Thomson came to bat for the Giants and hit a 3‑run home run winning the game for the Giants, and making baseball history.

In 1957, the owner of the Giants, Horace Stoneham (1903–1990) broke many New York hearts when he announced that he was moving the Giants to San Francisco. The Polo Grounds remained for seven more years, serving as home to the New York Mets for the 1962 and 1963 seasons. In 1964 the stadium was demolished and now the Polo Grounds Towers, a housing project, occupies the site. All that is left of the original Polo Grounds is an old staircase on the side of the cliff that once led to the ticket booth.

Today, Coogan’s Bluff is part of Highbridge Park, which was assembled piecemeal between 1867 and the 1960s, with the bulk being acquired through condemnation from 1895 to 1901. The cliffside area from West 181st Street to Dyckman Street was acquired in 1902, and the parcel including Fort George Hill was acquired in 1928. The park extends from 155th Street in North Harlem to Dyckman Street in Washington Heights/Inwood. The Friends of Highbridge Park are involved in preserving the park’s history and the New York Restoration Project has cleaned the park and restored its trails.2

Paul Robeson Residence

The Paul Robeson Residence, a National Historic Landmark, is located at 555 Edgecombe Avenue in New York City.

Paul Robeson (1898–1976) — actor, singer, civil rights advocate — lived in an apartment in this 13 story apartment building from 1939–1941, upon his return from living and performing in Europe.

Paul Robeson was a gifted student and athlete while attending Rutgers University in New Jersey. He was a brilliant Phi Beta Kappa student, two time All American football player (1917–1918), and won honors in debating and oratory. He graduated from Columbia Law School but gave up law to pursue a career in singing and acting. Robeson performed on Broadway, and is noted for his leading roles in Othello and Eugene O’Neill’s play, Emperor Jones, and his stunning rendition of the song “Ole Man River” in the musical Showboat. In 1934, he visited the Soviet Union, where he felt fully accepted as a black artist. During World War II, he entertained troops at the front and sang battle songs on the radio.

In 1937, Robeson wrote, “the artist must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery. I have made my choice. I have no alternative.” He continued this fight for freedom, both political and artistic, until his death in 1976.

Despite his war efforts, he was labeled “subversive” by McCarthyites, who were wary of his earlier trip to the Soviet Union, his support of the 1947 St. Louis picketing against segregation of black actors and a Panama effort to organize the mostly-black Panamanian workers. Robeson began receiving death threats from the Ku Klux Klan while campaigning for the Progressive Party candidate in the 1948 presidential election. When he publicly opposed the Cold War, even the national secretary of the NAACP questioned his loyalty as an American. Connecticut state officials also went to court to prevent him from visiting his family home in Enfield. Undaunted, Robeson formally denounced the action and on August 27, 1949, traveled to Peekskill, New York, to sing before a group of African American and Jewish trade unionists. A KKK-led riot canceled the concert but Robeson returned the following week with 25,000 supporters. A “human wall” protected Robeson while he sang, though afterwards many of the concert goers were ambushed and beaten while local police and state troopers stood by.

In March 1950, NBC barred Robeson from appearing on a television show with Eleanor Roosevelt. Concert halls closed their doors to him, and his records began to disappear from stores. After eight years, an international outcry, and the Supreme Court’s reversal of the same situation for the artist Rockwell Kent in 1958, Robeson won.

The High Bridge

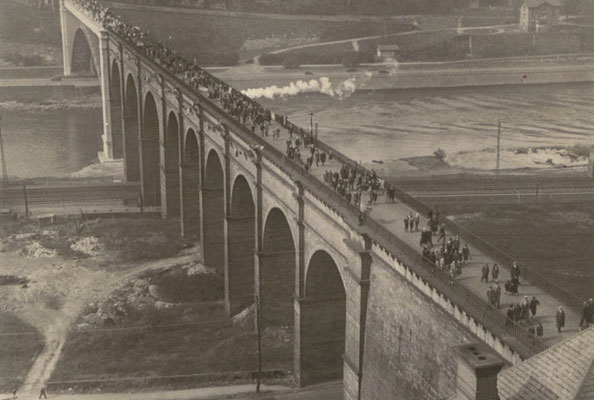

The High Bridge was built in the mid-19th century as part of the Croton Aqueduct system, which carried water from the Croton River in Westchester down to Manhattan. When you cross the bridge, you will be walking above the aqueduct’s original pipes, which still lie beneath the walkway of the bridge.

When the bridge first opened in 1848, 35 years before the Brooklyn Bridge, it was hailed as a marvel of civil engineering. Designed by engineer John B. Jervis, who worked on the Erie Canal, the bridge rises 138-feet tall and stretches 1,450-feet long, making it the longest bridge in the United States when it was completed.

Modeled after a Roman aqueduct, the bridge cost $950,000 to build, and it was part of the Old Croton Aqueduct System, built to provide the growing metropolis with a vital supply of fresh water from Westchester’s Croton River. Concern about the spread of disease, notably the repeated cholera epidemics, and memories of the Great Fire of 1835, which ruined most of lower Manhattan, also served as motivating factors for its construction.

The bridge opened to carry the aqueduct across the Harlem River in 1848, and its walkway was completed in 1864, making it a popular spot to promenade on a nice day. The bridge achieved fame as an attraction for New Yorkers and tourists and a favorite subject for artists and photographers, a sort of 19th century High Line. The walkway’s popularity led to the building of hotels, restaurants and amusement parks in the vicinity.

Equally popular were boat cruises up and down the river, and racing competitions for crew boats. Later, once the Harlem River Speedway was opened in 1898, sightseers strolled along the new waterfront esplanade in the cool breezes and watched horses and buggies fly by.

After construction of the Major Deegan Expressway in 1956 and the Harlem River Drive in 1964, public use of the waterfront faded. The river became polluted, paths were blocked, and the pull of the parks on the water’s edge vanished. In the 1970s, public access to the bridge was discontinued.

Local pressure to reopen the bridge began soon after, and eventually, groups such as The High Bridge Coalition were able to coalesce that support into a citizen-led campaign to restore the High Bridge and its neighboring parks. In 2012, work began to rehabilitate the bridge, and it was reopened in June 2015.

Read more about The High Bridge here.

This text is taken from the Morris-Jumel Mansion website. ↩

This text is part of Parks’ Historical Signs Project and can be found posted within the park. ↩